I believe that I first encountered Rimsky Korsakov’s “Flight of the Bumble-Bee” (FOTBB) composition before I began junior-high band in the eighth (8th) grade. I was trying to decide which band instrument I wanted to play. I had been studying piano for several years by this time.

In addition to pianos, there were several instruments in our house: an accordion (I played a little), a saxophone (it smelled bad), and a trumpet. My Mother had played both the trumpet and saxophone during college and during her time teaching school.

I began playing the trumpet and encountered the “Flight of the Bumble-Bee” in a trumpet book of Mother’s. I didn’t continue to play trumpet. And, I never played FOTB again until 2008, when I recorded the piano-solo version.

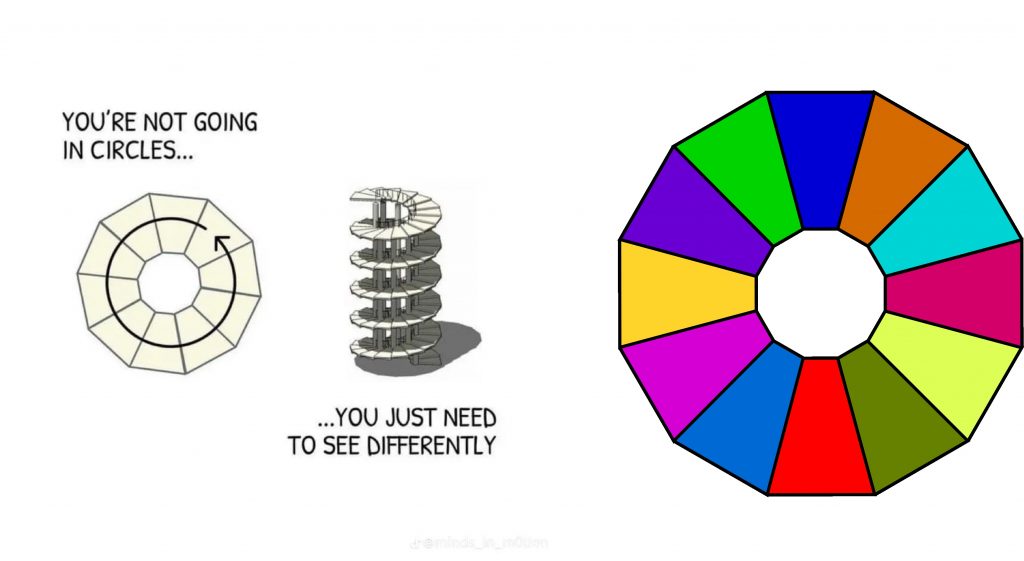

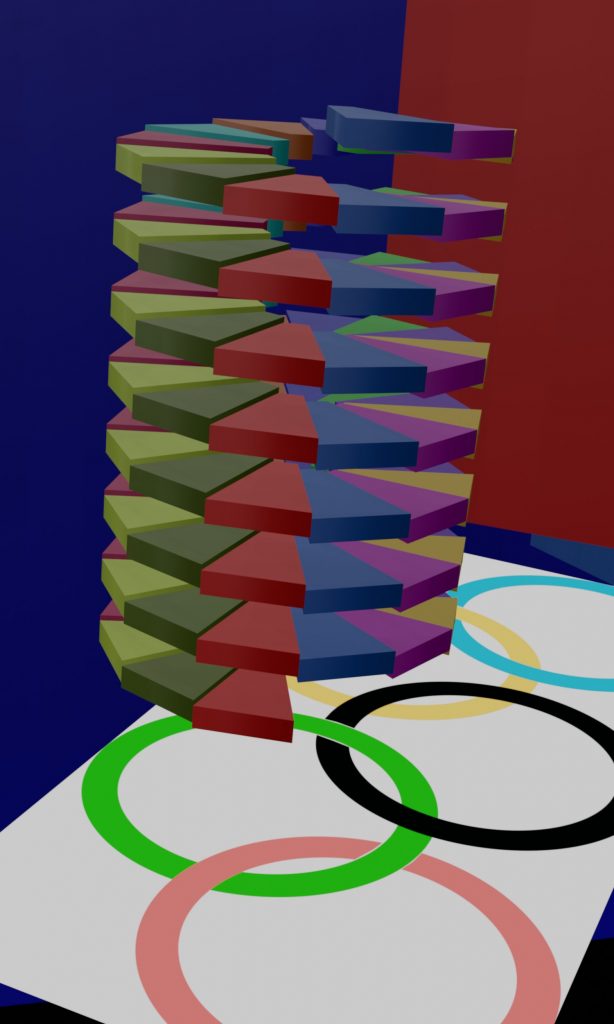

I recently experienced a “Eureka Moment” in my animation evolution —by learning to use MIDI note information to control aspects of my musical animations in ways that I will continue to explore. As I continue to think about good candidates to demonstrate my recent “Chromatic Pitch Spiral” (CPS), I remembered “Flight of the Bumble-Bee.” It fulfilled several of the characteristics I was seeking for an initial musical selection: single-instrument, polyphonic (multiple notes at the same time), and is something that could “showcase” the usage of my Spiral.

I hope that you enjoy my presentation —and, stay tuned !!!

Like hour-divisions on a clock, there are 12 chromatic pitches per octave. All of music can be reduced to that —twelve (12) different pitches —one revolution around a traditional “pitch wheel.” Students of music-theory know the “Circle of Fifths,” which is an arranged ordering of a “pitch wheel.”

Like hour-divisions on a clock, there are 12 chromatic pitches per octave. All of music can be reduced to that —twelve (12) different pitches —one revolution around a traditional “pitch wheel.” Students of music-theory know the “Circle of Fifths,” which is an arranged ordering of a “pitch wheel.”

Recent Comments